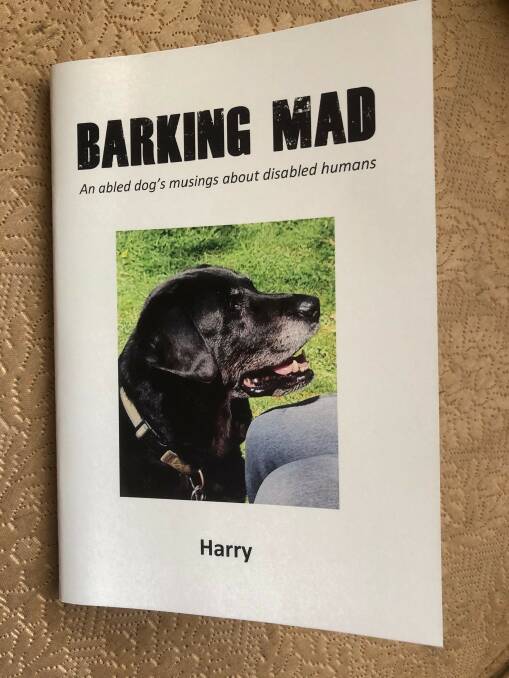

A Cootamundra author with a disability has been helped by his employer to write his first book, an 84-page collection of musings entitled Barking Mad.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

According to his employer, the author, a black Labrador guide dog called Harry, suffers from the disability of being unable to reach the letter "q" on the keyboard with his paw.

"I helped Harry whenever he needed to write a word with 'q' in it, otherwise the book is all his work, his ideas and everything," said Ross Fitzell, who has employed Harry for the past 10 years as his guide dog.

All jokes aside, Ross himself suffers from a disability, having been suddenly struck blind nearly eleven years ago, at the age of 64, with a rare auto-immune condition that rapidly denied blood supply to his optic nerves.

Total blindness hasn't stopped Ross from enjoying his life, and it was a happy day in the Fitzell household yesterday when the first 200 copies of Harry's book arrived in boxes from the Atlas Printing Works, ready for distribution around town.

With Ross bearing all the printing costs himself, all proceeds from the sale of Barking Mad will go to Guide Dogs NSW/ACT.

"It's not too much for me to give a little bit back again," said Ross, "Harry has given me ten years of his life - and he's my best mate, when all's said and done," Ross observed.

Copies of the book will be on sale from today at a couple of coffee shops where Harry and Ross are frequent visitors, and at other venues as time goes by.

The recommended retail (donation) price is $15. People can pay on the spot, or can take it away and pay on an honour system by donating via the Guide Dogs web address on the back cover.

Anyone who'd like to order a copy can email Harry at dotdog20@icloud.com or call him at 0416 55 66 10.

Barking Mad is subtitled An abled dob's musings about disabled humans, and consists of some 36 "episodes" covering a wide range of topics Harry has found of interest since 2011 (he started working for Ross in 2010).

Titles of episodes include "Episode 17. About honesty, poetry, rewards and punishments" and "Episode 21. About making the world a better place".

Dropping the pretence of Harry's authorship (handy if you're sued for defamation or anything), Ross explained that he started writing the book almost by accident.

"The first little bit was prepared as a possible article in the revered Cootamundra Herald," he recalls. "But they didn't accept it so it was sent out by email.

"The email was well received, so I started creating and issuing them regularly, and in the end there were about 5,000 readers of Harry's emails.

"Every email went out with permission to email it further, and I got emails back from Venezuala, Equador, US, Canada, Scandinavia North America.

"I only ever got two saying stop sending me this rubbish.

"One feller said 'I'm not interested in this, can you take me off your mailing list' and I replied 'You're actually not on my mailing list, this was sent to you by somebody that actually likes you!'.

"The other was one I sent accidentally to a woman I'd already deduced she had a bit of a personality issue, either with guide dogs or with me.

"Two negatives out of 5,000 is not too bad."

Emails became "yesterday's technique", so Harry moved to a website.

"That website,in turn, turned into this book," Ross said.

"I think someone asked me to turn it into a book - it might've been Harry who asked me - it just seemed to be a logical way to do it.

"The reaction so far is people are very excited, saying it would be a nice gift, nice to read and all that.

"The only thing is some people think that because it's about a dog or written by a dog it might be good for children, but it was never intended to be a children's book.

"It's about disabilities and dogs' reactions and Harry's boss's reactions to difficult situations and how they should be handled.

"How do we handle stepping off kerbs and walking into light poles, avoiding bushes? - and all that sort of thing.

"And not just vision deficiency but disabilities at large and of course the government's reaction to it. It's difficult to talk disabilities without talking government and some of the comments there, Harry's not terribly enamoured with the various levels of politics.

"For example issues he raised with the local council back in 2011 still haven't been considered or rectified and they're things that are dangerous for somebody with no sight, and I'm not the only one.

"But also for frail elderly people, mums with prams and strollers and people walking generally, traffic issues are not really good and not terribly well managed, I think - so Harry makes a few comments about those sorts of things.

"But he says lots of nice things too and talks about ice cream and what we do on good days walking out in the sunshine.

"Kids might enjoy the drawings but it's really at an adult level - people getting knocked over at intersections or the person he calls the boss, that could be me, walking into a branch - that was to do with languages.

"Harry's a very erudite and intelligent, and indeed loquacious, dog and he knew at the time 105 words so I'd talk to him and he understood that.

"But he looked at me one day - he's always on my left hand side - and he looked up and apparently he said 'boss watch your head' but I heard it as 'woof' and next I walked into an overhead branch and went head over turkey.

"It's really just meant to talk about the life of a guide dog and a guide dog handler."

Ross says he teaches Harry things by repetition, for example if a chemist shop changes location, if there's any confusion I might take him inside the door of the shop and say 'chemist' and give him a treat and walk back five or six metres.

"And we'll do it four or five times, him getting a treat every time. And then next time I can walk out my front door and say 'find chemist' and he'll just go all the way to the chemist shop and walk in the door, which is just amazing."

While January 26 for most people means Australia Day, for Ross it has a much more powerful personal meaning: it's the day in 2010 he went blind, suddenly, stricken by a rare condition of the arteries called called giant cell arteritis.

This disorder arose because his immune system started producing very large red blood cells to counter an antigen, or enemy, it "thought" it had detected in his bloodstream.

"There was no enemy, but the giant cells were so big they couldn't get through the optic nerve, so I lost blood supply to the optic nerves."

In almost all cases of giant cell arteritis, doctors are able to stop its progressing with treatment, but in Ross's case he was told almost straight away that the damage could not be treated and he would remain permanently and completely blind.

"I was in hospital for three weeks while preparations were made for a guide dog and support network. and the professor who was treating me was surprised that I wasn't grieving my loss of sight," Ross said.

"He said 'if there's one thing we could do with you it would be to bottle your enthusiasm' and he also told me he'd been practicing for 40 years and I was the first one that had total loss of sight.

"He said he had only read of one other case, and that was Ray Charles the singer.

"So I said 'so that means that if Ray Charles and I were up on stage together singing you wouldn't be able to tell us apart, would you?

"He seemed to think that was pretty funny".

In the acknowledgements page, Ross said he had had incredible help and support from lots of people, especially Alan Salmon, Jim Nolan and illustrator Alan McClure.

Ross said it had been fun helping Harry write the book and Harry had already finished two new episodes for a sequel, which he intends to call Barking Mad, Too.